Netent

Big Time Gaming

No Limit City

Fat Panda

PlayStar

Miki World

AsiaSigma Lottery

Pragmatic Play

Habanero Gaming

Spade Gaming

Saba Sports

Joker Gaming

PG Soft

KingMaker QM

One Game

AE Gaming

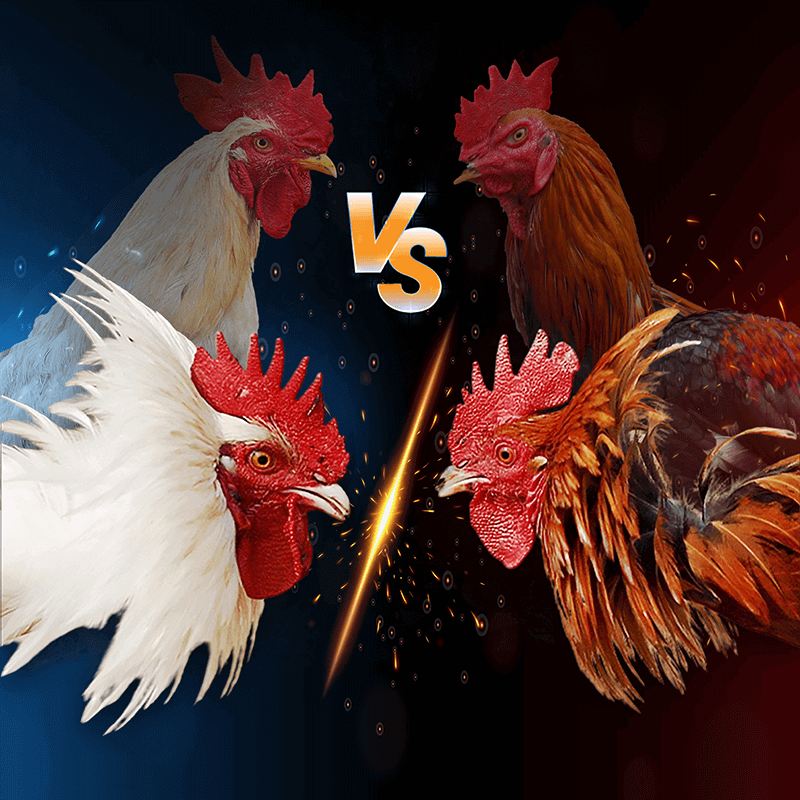

SV388

JDB Slots

ION Casino

SBO Sports

CQ9

WM Casino

KS Gaming

AFB Sports